Mary Kennard (1850 – 1936)

05 October 2018

Mary Kennard, a prolific novelist and early advocate for women in motoring and motorcycling, made her mark in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Explore her pioneering journey from novelist to motoring trailblazer.

Patrick Collins – Research and Enquiries Officer

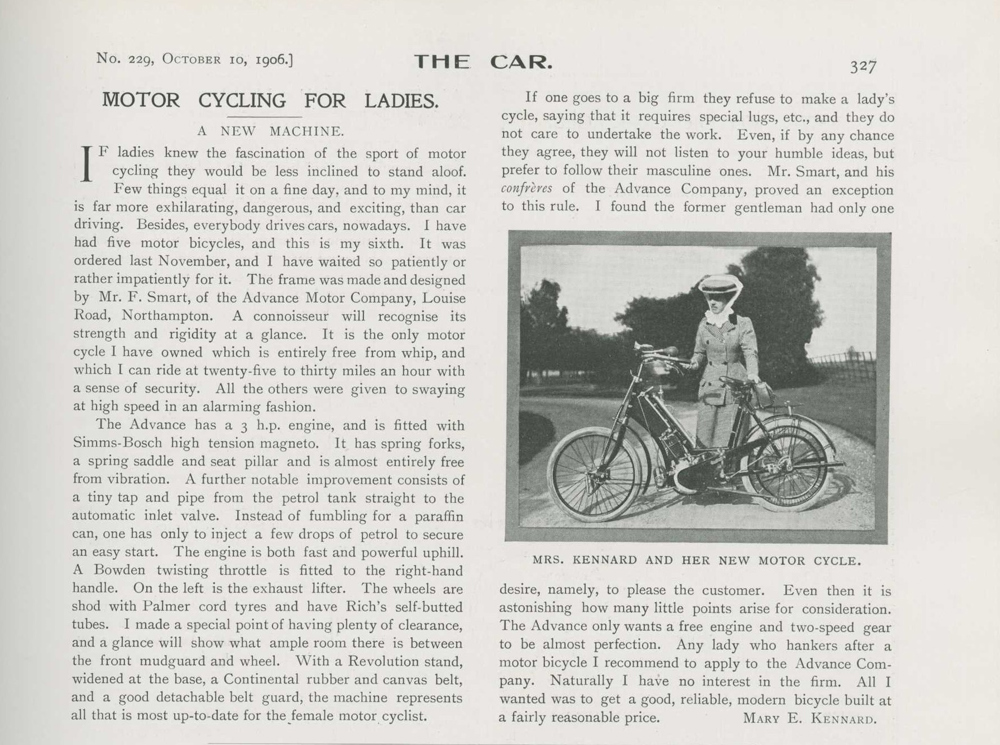

A name that appears frequently in the motoring press in the early years of the 20th century is that of Mary Kennard. At a time when few ladies drove she became a leading advocate of both motoring and motorcycling for women.

The wife of Edward Kennard, a land owner and former journalist, Mary Kennard made a name for herself in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain as a prolific novelist, writing as Mrs Edward Kennard. Her writing was based mainly around country sports. She was one of twenty-four authors, among them Bram Stoker and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who contributed to the The Fate of Fenella in 1892. Like many of the period, she was a keen cyclist, writing A Guidebook for Lady Cyclists in 1896. In 1899 she began driving in a 3½hp Benz and in the years that followed became increasingly involved in advocating motoring.

Mr Kennard was himself a well known early motorist and was the owner of the first production Napier, the car driven by SF Edge in the 1,000 Mile Trial of 1900. Mrs Kennard, although not registered as an official entrant, completed most of the route of the trial at the wheel of a De Dion Bouton Voiturette borrowed from Edge. Meeting with a minor incident near Northampton in the latter stages, she retired to the family home at Market Harborough, later receiving a reprimand from the car’s famous owner for driving too fast for the circumstances in which she found herself.

Mary Kennard was both a keen motorist and hands-on mechanic, reputedly having her own overalls which she wore when carrying out repairs, assisted by Brooks her chauffeur.

A regular contributor to the motoring press, Mary Kennard wrote frequently for Car Illustrated, John Scot-Montagu’s (later 2nd Baron Montagu of Beaulieu) weekly journal of travel by land, sea and air, on both four and two-wheeled subjects as in this piece from 27th August 1902:

“I greatly prefer the motor bicycle to the three-wheeler. Certainly something is sacrificed in safety and stability, but the gain in handliness, in weight, and having a single track is enormous.”

Although generally advocating motoring for women, sometimes the tone of her writing was, to our modern eyes, a little self defeating as in her comments after trying a new 20hp Maudslay, a large and powerful car and not the easiest for anyone to handle, in the issue of 3rd September 1902:

“The clutch spring was so stiff that my feminine strength was hardly sufficient to depress it. So after a most interesting experience and driving some five or six miles, I thought it more prudent to resign the helm to the owner.”

On the whole, however, Mrs Kennard’s advice to fellow lady motorists was positive:

“One of the greatest tests of good driving is to be able to inspire one’s passengers with a feeling of confidence, especially if they are timid… It is a responsibility for a woman to steer a car full of strangers, and she should rise equal to the occasion.” (Car Illustrated 4th June 1902)

Seemingly ever at the forefront of the latest motoring developments, by 1914 Mary Kennard had adopted the trend for light cars, appearing in the pages of the 2nd March issue of The Light Car & Cyclecar magazine extolling the virtues of the new breed of small cars for the lady motorist. She advocated the new breed of light car for women drivers whom she clearly felt were possessed of a natural mechanical sympathy:

“A woman with an ear for music has also an ear for an engine. She understands its beat, knows when to accelerate and when not.”

Mary Kennard died in 1936, by which time her success as a novelist and pioneer motorist had been long forgotten.

Discover more from our The Drive for Change project, exploring the connection between motoring and the suffrage movement, and the emancipation of women in the broader context.

Subscribe for updates

Get our latest news and events straight to your inbox.