Wakefield and Castrol

Explore the life of Charles Cheers Wakefield, a key supporter of Britain’s speed ambitions. In addition, the success of his Castrol Oil and how it used Britain’s achievements to place itself as the premier product for high performance racing will be examined.

Charles Cheers Wakefield was a wealthy industrialist who helped propel Britain’s land speed ambitions.

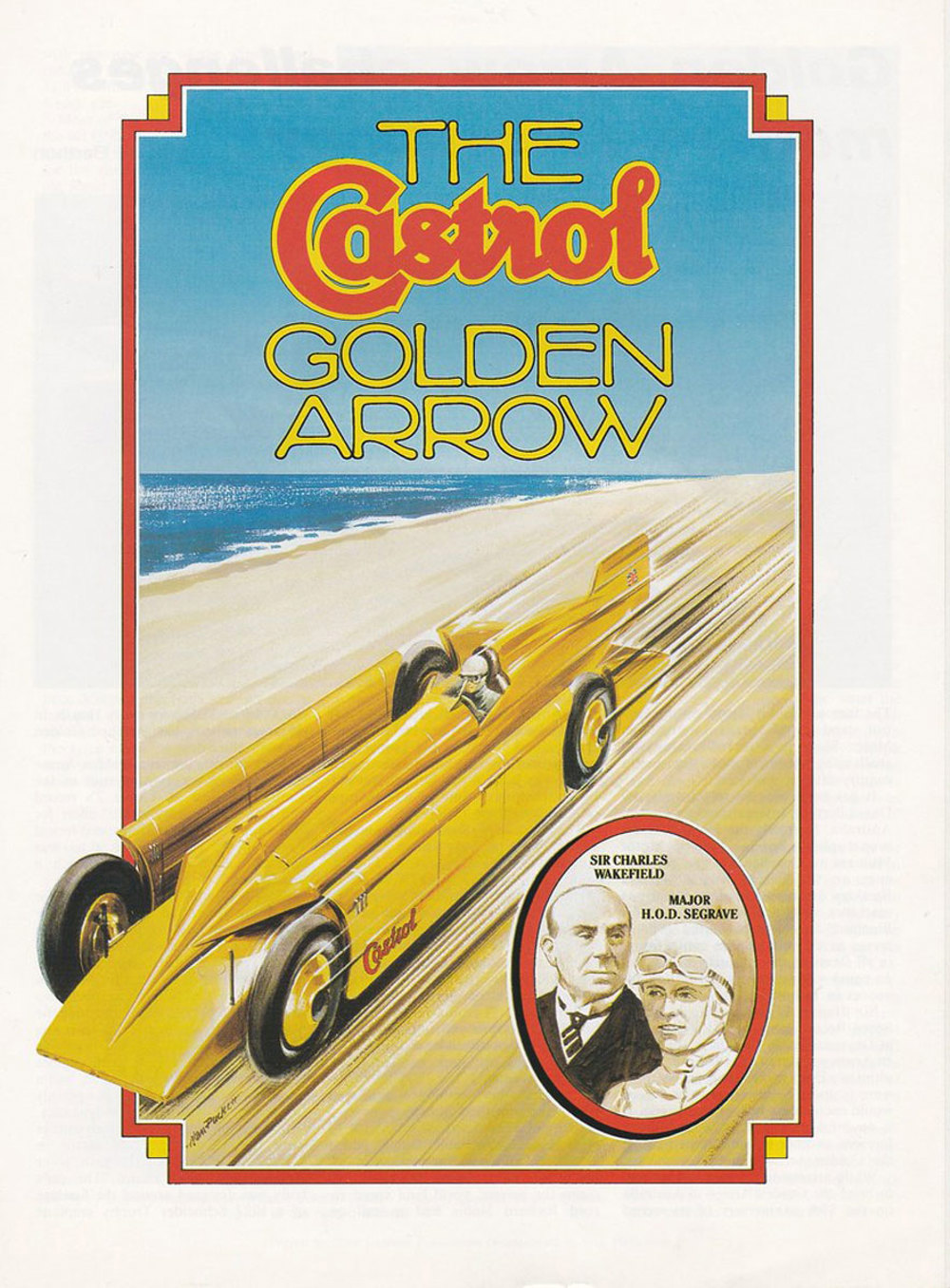

He participated in this through financial sponsorship of Segrave’s Golden Arrow in addition to creating speed trophies to promote competition.

This article explores Wakefield’s rise and how he obtained the power and wealth necessary to exert such an influence on the motoring world.

Wakefield’s Early Life

Wakefield was born in December 1859 in Liverpool to Margaret and John Wakefield.

He was educated at Liverpool Mechanics Institute, which likely promoted his interest in engines from a young age. In his early career, he worked as an oil-broker where he travelled the world on ships such as the RMS Campania, his work often led him to New York.

Rising Wealth and Status

In 1899 Wakefield established the C.C Wakefield and Co. Company, which dealt with lubricating oils and appliances. It was through this company that Castrol was established within the automobile industry. The name ‘Castrol’ was decided due to the lubricant containing Castor Oil.

The oil was known for being able to ensure that engines remained efficient even at high temperatures, an important feature for competitive race cars and land speed record vehicles. This breakthrough put Castrol Oil on the automobile market.

Castrol Oil quickly became promoted as a technological breakthrough given its characteristics and led to an enormous amount of wealth for Wakefield. Afterwards, he used his new influence to shape the motorcar industry.

Outside of the motor oil enterprise, Wakefield embarked on supporting children’s’ and educational charities in London such as the Haberdashers’, Cordwainers’ guilds.

In addition, Wakefield’s supported the Gardeners’ and Spectacle Makers’ companies. He also took an extended interest in the aviation industry, and supported Sir Alan Cobham by assisting aviation groups and charities.

These causes did not go unnoticed. First, Wakefield became an alderman in 1907 and was knighted in 1908 for his services to the City of London. By 1915 he became Lord Mayor and by 1917 he had been made a baronet.

Golden Arrow, the Wakefield Trophy, and Promoting Castrol

Wakefield’s interests also extended to competitive causes, with a particular focus on the racing and aviation land speed records.

To promote this, Wakefield established the ‘Wakefield Gold Trophy’ in 1928 and financed a yearly £1,000 prize to the holder of the ‘Motor Car Speed Record’.

Wakefield also engaged in a partnership with Segrave and Golden Arrow by providing extensive investment in the project. However, this wasn’t a purely charitable endeavour.

Sir Henry Segrave’s 1929 triumph of breaking the land speed record was used by Wakefield to advertise the benefits of Castrol Oil as show in the poster above. Overall, he made sure to use the world-wide attention surrounding motor car and speed record achievements to promote Castrol.

He also owned the first two Miss England powerboats, also driven by Segrave. The sudden death of Segrave and Percival Halliwell in 1930, during their attempt to set a new record, led Wakefield to pay for the funeral of Halliwell.

Such generosity continued into the 1930s when he was recognised for his charitable character and made a viscount. By 1937, he had established the Wakefield Trust to contribute to charitable causes in East London.

Charles Cheers Wakefield keenly understood the power of advertising. He was fascinated by sponsorships and the role they played in promoting his company.

This article will explore how Castrol made the most of its advertising in addition to its association with Golden Arrow and later land speed record vehicles.

Wakefield was no stranger to spectacle and in 1922 he chose to assert Castrol’s dominance in the lubricant market through air advertising. This may be one of the first examples of such a technique. In this image you can see the name ‘Castrol’ has been written in the sky.

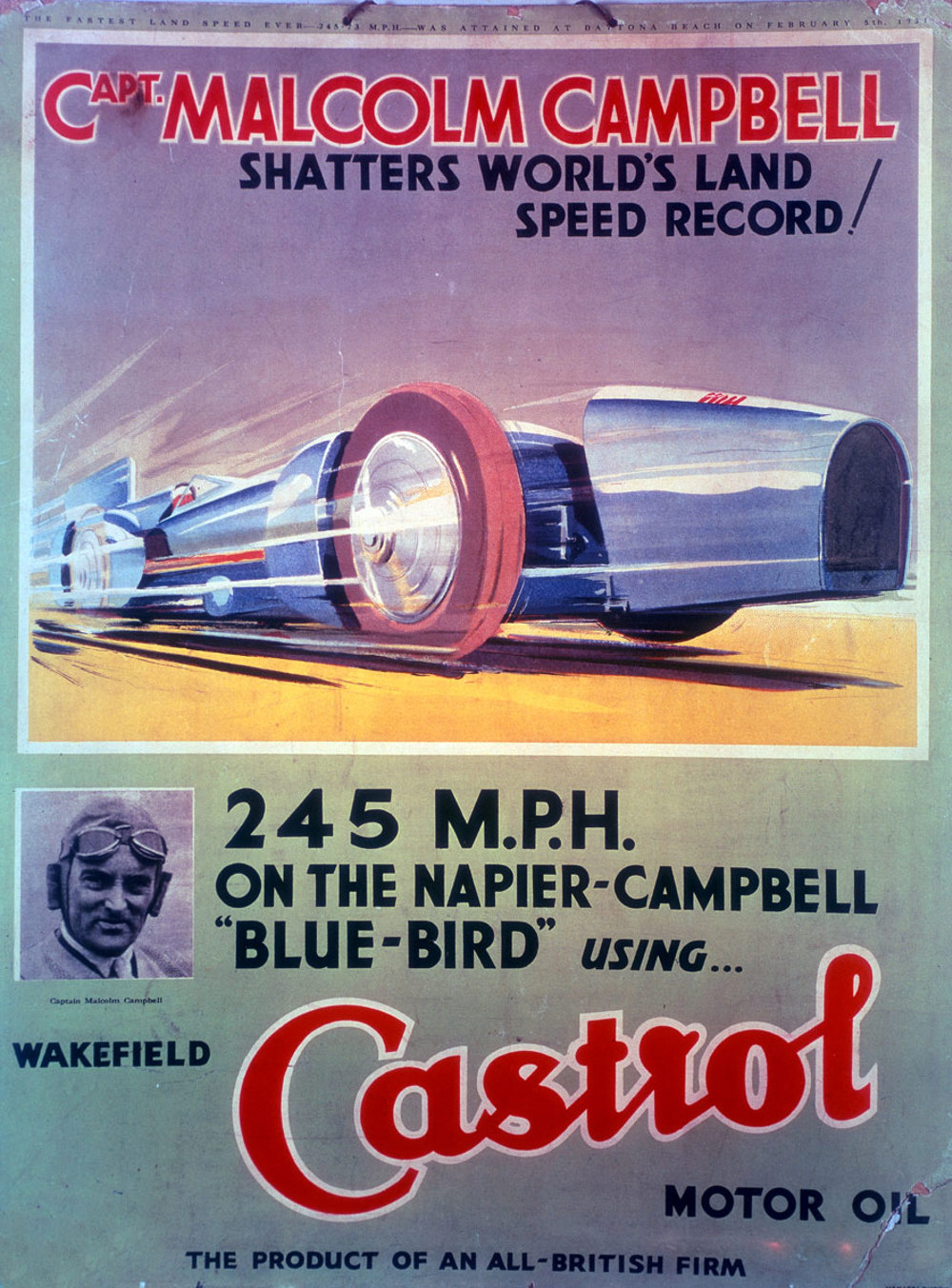

Wakefield promoted the increasingly competitive atmosphere surrounding Britain’s land speed record attempts and associated Castrol Oil as a key component to British success. This was seen with Henry Segrave’s 1927 achievement, when he broke the land speed record in the 1000hp Sunbeam.

The poster above shows how Castrol made the most of patriotic impulses, asserting itself as part of the ‘all British triumph’.

Castrol Oil became closely associated with Golden Arrow due to Wakefield’s sponsorship of Henry Segrave’s attempt. There are an extensive set of commemorative materials ranging from posters to pamphlets which celebrated British land speed achievements whilst promoting Castrol Oil.

Overall, between the 1920s and 1930s: the land speed record was broken 23 times and 18 of those broken records were achieved with the sponsorship or use of Castrol Oil. As a result, after Golden Arrow’s victory, Wakefield commissioned a new Castrol logo as part of a campaign to portray the fluid as the ‘world’s fastest oil’.

Further Reading:

Castrol Company. “The History of Castrol.” Castrol Classic Oils. Accessed 21st May 2021. https://www.classicoils.co.uk/history

Subscribe for updates

Get our latest news and events straight to your inbox.