Tours

Discover how National Tours were used by the women’s suffrage movement.

National Tours

Tours were used by the women’s suffrage movement throughout the early twentieth century to spread their message up and down the country.

Tours took place as early as 1892, when the Primrose League Ladies’ Grand Council toured in their van through Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire, distributing leaflets and making speeches to areas which were otherwise too difficult to access during the normal course of the election.

Into the twentieth century, the women’s suffrage movement adopted this method of campaigning, reaching a wider audience.

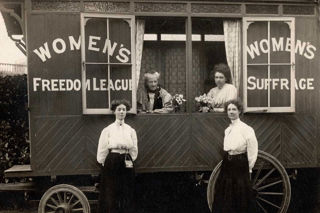

Initially, caravans, drawn by horses, were used to travel the country. In May 1908, for example, the Women’s Freedom League had a caravan specially built for their personal national tours.

It was branded with their name, and the words “Votes for women” and “Women’s suffrage”. As twentieth century transport developed, however, suffrage movements recognised the benefits of using the more rapid motor car for their national tours.

In 1905, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) gave a grant of £30 to the Lancashire and Cheshire Women Textile and Other Workers’ Representation Committee towards the cost of a motor car for the special outdoor campaign.

In the following years, many other women’s suffrage associations purchased a motor car.

The national tours served to inspire both women and men across the country to support the cause of women’s suffrage, and encourage the creation of supporting organisations. The women enjoyed life in the open-air; it gave them a new sense of freedom and put their message on the national stage.

The motor car was effective and hastened the movement, without it, it is fair to say that the Suffrage campaign would have moved a lot slower.

Sources:

Crawford, E., The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (London: University College London Press, 1999), p.97.

Credits:

Images courtesy of the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics (The Women’s Library, LSE/Flickr)

Caravanning

Touring in a caravan emerged as a popular means of spreading political messages into the twentieth century. The women of the suffrage movement used this to their advantage, and by the summer of 1908, caravanning became an effective and essential part of the national campaign.

Beginning in Beattock, South Scotland on the 22nd July 1907, a group of students from Newham College, at the University of Cambridge, spent the summer travelling around the UK in a horse-drawn caravan promoting the cause of women’s suffrage.

The group was led by Frances Rendel and Ray Costelloe, and over a thousand people heard their suffrage message. In 1908, their Roll Letter reflected that “the police always came” and that the audiences were mostly working men, and sometimes women.

“Four of us spoke and the whole meeting lasted about an hour and a quarter”. They also commented, however, eleven years before suffrage was achieved, that they were “convinced that the average English working man is perfectly ready to approve of votes for women”.¹

In Ray Costelloe’s personal letters she reflects on her time touring the country, stating that it was “the greatest possible fun and the least possible bother" especially due to the practicality of using a caravan. The police who attended “were charming, and [surprisingly] all in favour most enthusiastically”. In Bowness, Costelloe draws attention to a “crowd of small boys”, who followed the caravan “yelling for votes”. Although “their enthusiasm was not very serious…they pushed the van up a long steep hill, and we told them they had helped forward the cause”.²

Helen Fraser joined the WSPU in 1906, soon becoming an organiser, and established an intensive suffrage campaign across Scotland. Despite this, when hearing of Mrs. Pankhurst’s ‘stone-throwing’ campaign, she resigned from the WSPU and took up allegiance to the NUWSS, engaging on a national tour from Selkirk to Tynemouth in a caravan in 1908. It was this tour that inspired the formation of numerous affiliated local societies in the Highlands.

Also in 1908, Emilie Gardner and Margaret Robertson toured for the NUWSS through Yorkshire in a caravan. As an excellent public speaker, Robertson embarked upon numerous caravan propaganda and caravanning tours, stopping along the way to give open air talks, on topics such as pay inequality as well as the right to vote, peacefully promoting the cause for women’s suffrage. It is suggested that following Robertson’s tour to Oxford, in 1910 suffrage circles formed in the city.

In July 1908, the Kendal Mercury and Times published an article on the Suffragettes embarkment upon national tours. The paper commented that “all the suffragettes are not taking their pleasures sadly and longing for martyrdom in the shape of imprisonment, but some are combining business with pleasure by touring the most lovely parts of the country in a caravan”.

The ability to be able to use a caravan gave women a new found freedom, allowing them to escape their home towns and cities with a purpose. These women used the caravan to their advantage; “there was nothing of the wild hysterical style about them. They all spoke clearly and evidently in earnest”.³

References:

¹ Newnham College, ‘Newnham looks back to suffragist students who campaigned to get women the vote’ Newnham College, University of Cambridge (2015) [accessed 30/04/2018]

² ‘Ray Costelloe’s letters home during her caravan tour’ (7 July and 9 July 1908), held by The Women’s Library Collection at The London School of Economics, London.

³ Kendal Mercury and Times, ‘The Suffragettes at Kendal’, in Kendal Mercury and Times (July 1908).

Sources:

Cowman, K., Women in British Politics, c.1689-1979 (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p.94.

Crawford, E., The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928 (London: University College London Press, 1999), pp.96-97.

Crawford, E., The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain and Ireland: A Regional Survey (Oxon: Routledge, 2006), p.99.

Ewan, E., Innes, S., and Reynolds S., (eds.), The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women. From the earliest times to 2004 (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2006), p.127

Newnham College, ‘Newnham looks back to suffragist students who campaigned to get women the vote’ Newnham College, University of Cambridge (2015) [accessed 30/04/2018]

Credits:

Images courtesy of the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics (The Women’s Library, LSE/Flickr)

Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst of the WSPU began her tour in September 1909, touring the southern Highlands in the hope to inspire Scotland to join the Women’s Suffrage movement of Great Britain.

For four days the touring car worked its way up to the north, and on the fifth day they crossed the border, much faster than by caravan or foot.

American Alice Paul joined Mrs Pankhurst on her tour, reflecting that just riding in the WSPU touring car made the trip worthwhile; the car not only carried passengers, but “meaning” also. She remarks that “great meetings had been arranged for Mrs. Pankhurst”. “She would make one of her great speeches to enormous crowds; and then we would go on to the next stopping place”. Alongside grand speeches, the suffragettes also had plans to disrupt important ‘gentleman only’ events.

The touring Suffragettes enjoyed not only promoting their cause, but sight-seeing also – they experienced a freedom to explore the country and be active outside of the home, demonstrating their independence and satisfactory qualification for the vote.

Sources:

Fry, A. R., and Zahniser, J. D., Alice Paul: Claiming Power (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pp.86-89

The Great Pilgrimage

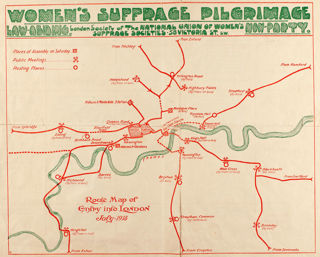

The Great Pilgrimage of 1913 was possibly the largest-scale public demonstration in support of women’s suffrage.

The event was proposed and organised by Katherine Harley, after she realised the importance of the whole country hearing about the cause of women’s suffrage straight from the women who passionately supported it.

Women, and some men, set out from across Britain, travelling along six major routes, with many smaller routes splintering from these, all heading towards London.

The 300 mile route was undertaken from mid-June until the end of July, with it not being uncommon for the women in the procession, deemed ‘Pilgrims’, to walk up to twenty miles each day.

As caravans were considered a great luxury, most women braved the summer heat and dust on foot. Nonetheless, a few notable caravans were used, including ‘The Ark’, which was Marjory Lee’s home throughout the Pilgrimage, and ‘The Sandwich’, which left Oldham at the same time as Lee’s caravan.

Some women, including the reporter commissioned by the Daily News, Vera Chute Collum, preferred to complete the Pilgrimage by horse. Others used bicycles, which were particularly useful for pedalling ahead of the main group and organising their arrival at the next destination. The occasional motor car or charabanc was also necessary for the more elderly or infirm supporters.

Along the way, the ‘Pilgrims’ encountered many inspirational women. For example, a vicar’s wife hosted the group for tea. She regaled the group with tales of her unusual life as a doctor and clergyman’s wife who drove her own motor car.

The Pilgrimage brought people from all walks of life together in support of women’s suffrage.

Lady Rochdale remarked that the women taking part ranged from duchesses to fish wives, with some bringing their children and even their husbands.

This diverse crowd of ‘Pilgrims’ sought to distance themselves from the militant suffragettes, meaning that they were encouraged to remain peaceful and non-threatening, even when faced with abuse from locals.

Sources:

Crawford, E., ‘Suffrage stories: ‘The Putney Caravans’’, Woman and Her Sphere (2012) [accessed 24 April 2018]

Graham-Jones, A., on ‘Women’s Hour’, BBC Radio 4 (1962) [accessed 18 April 2018]

Robinson, J., Hearts and Minds, The Untold Story of the Great Pilgrimage And How Women Won the Vote (London: Penguin Random House, 2018).

The National Archives Website, 'Women’s Suffrage' [accessed 20 April 2018]

Credits:

Images courtesy of the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics (The Women’s Library, LSE/Flickr)

‘Help or Hindrance?’

Often this question arises concerning the use of motor vehicles and caravans within the Suffrage Movement.

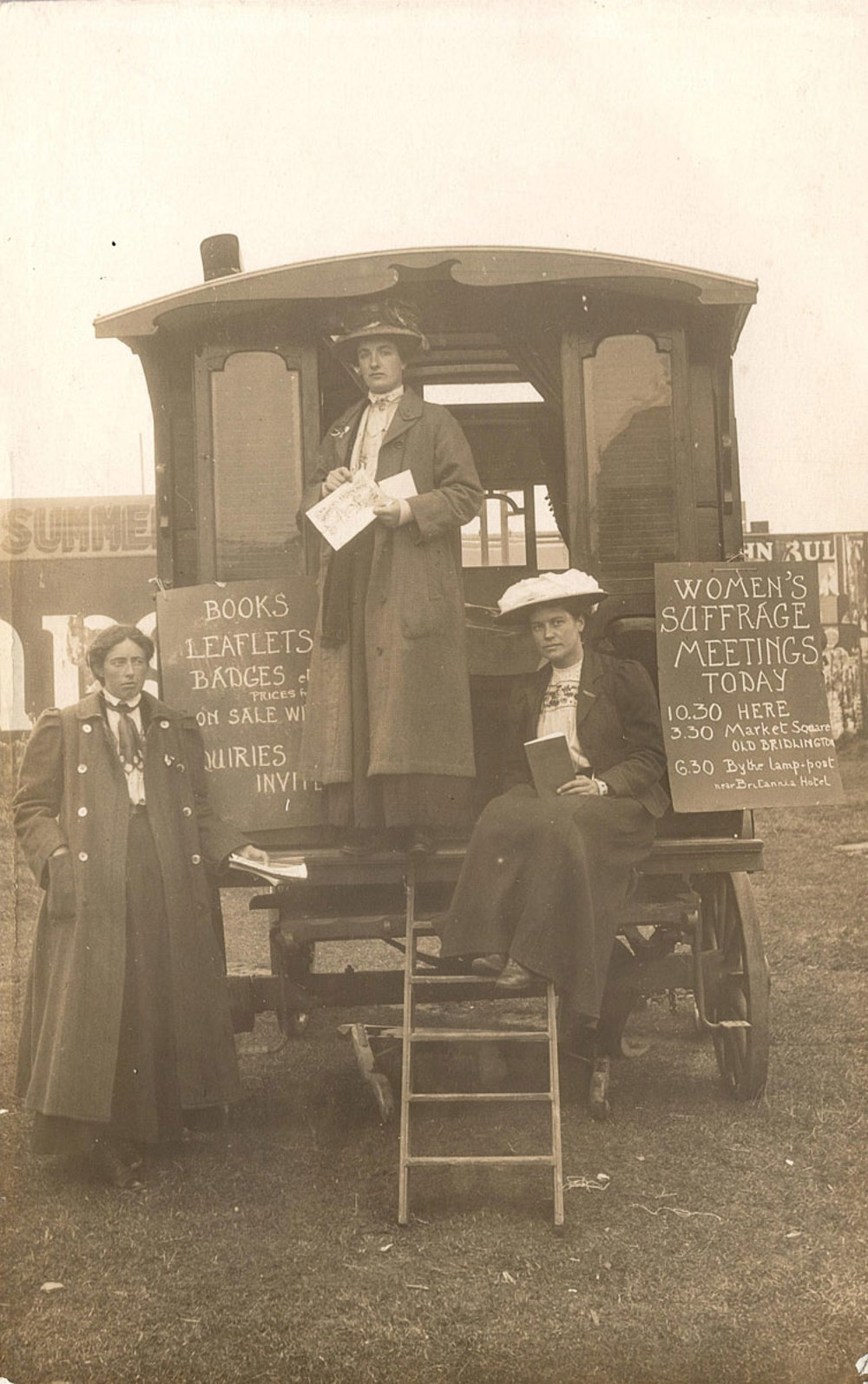

Caravans were first used by the non-militant suffragists as a means of conducting national tours, often termed ‘Pilgrimages’, travelling across Britain and raising awareness of their cause.

It may seem that a motor vehicle would tremendously aid campaigners; for example, a vehicle served as a blank canvas from which supportive posters could be hung and subsequently paraded across the country.

Additionally, many supporters of the cause sought to support the national tours, but many could not walk far, therefore motor transport allowed them to join in without pain or injury. Alice New’s mother, for example, drove a few of these pilgrims at the end of the procession of women in the 1913 Great Pilgrimage. Gladys Duffield joined them in a Charabanc.

However, did the use of motor vehicles actually undermine the suffragists’ efforts? National tours involved an element of self-sacrifice, as if the campaigners themselves were pilgrims denying themselves luxury to demonstrate their passion for their cause. The emphasis on walking also countered the perception that Edwardian women were opposed to physical exertion and lacking stamina.

Therefore, although some motor vehicles had to be used, they were relegated to the back of the procession to lessen criticisms that it was more of a joy-ride than a pilgrimage.

Regardless, it is likely that without the early horse-drawn caravan, suffrage campaigners would have been unable to complete their national tours.

The use of a vehicle enabled their message to be spread faster and to a wider audience, whilst also providing the suffragists with a place of refuge when they encountered abusive criticism from locals, which saw them pelted with dead rats, rocks and rotten eggs.

Sources:

1911 Census multiple authors, ‘All Census & Electoral Rolls results for Suffragette Absent Away’, Ancestry (2011) [accessed 18 April 2018]

Crawford, E., ‘Suffrage stories: ‘The Putney Caravans’’, Woman and Her Sphere (2012) [accessed 24 April 2018]

Graham-Jones, A., on ‘Women’s Hour’, BBC Radio 4 (1962) [accessed 18 April 2018]

Robinson, J., Hearts and Minds, The Untold Story of the Great Pilgrimage And How Women Won the Vote (London: Penguin Random House, 2018).

The National Archives Website, 'Women’s Suffrage' [accessed 20 April 2018]

Subscribe for updates

Get our latest news and events straight to your inbox.