WW1

Explore the impact that the First World War had on the campaign for women’s suffrage

The Amnesty of August 1914 emerged as a result of Britain’s dedication to the war effort pardoning hundreds of persons associated with the Suffrage Movement.

The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed in 1897, and as a result of impatience with the NUWSS’s passive tactics, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was established in 1903. Emmeline Pankhurst founded this group as she believed that more drastic measures needed to be undertaken, leading to the emergence of the militant suffragettes.

One notable suffragette was Norah Smyth who joined the WSPU in 1912, and during her time within the movement was arrested for assault, and subsequently organised disguises to avoid further arrests on public order charges.

Once the war broke out in August 1914 however, most suffrage societies suspended their militant tactics to focus on the war effort, filling the occupations of men sent to fight. In response, the Home Office compiled a list of suffrage campaigners who were being granted amnesty, which included the names of over one hundred men.

Norah Smyth’s name featured on this list, and she was given an official pardon for the offences she committed in support of the women’s suffrage movement.

This amnesty highlights how patriotism and support of the war effort became more important than the campaign for women’s suffrage, even to some suffrage campaigners themselves. The more than one thousand men and women’s names on the list also underlines how many people believed the suffrage movement was important enough to risk their jobs and families in support of it.

Sources:

Ancestry.com, ‘England, Suffragettes Arrested, 1906-1914’, Ancestry (2015) [accessed 17 April 2018]

Robinson, J., Hearts and Minds, The Untold Story of the Great Pilgrimage And How Women Won the Vote (London: Penguin Random House, 2018).

The National Archives Website, 'Women’s Suffrage' [accessed 20 April 2018]

Credits:

Image courtesy of The Library of Congress (The Library of Congress/WikiCommons)

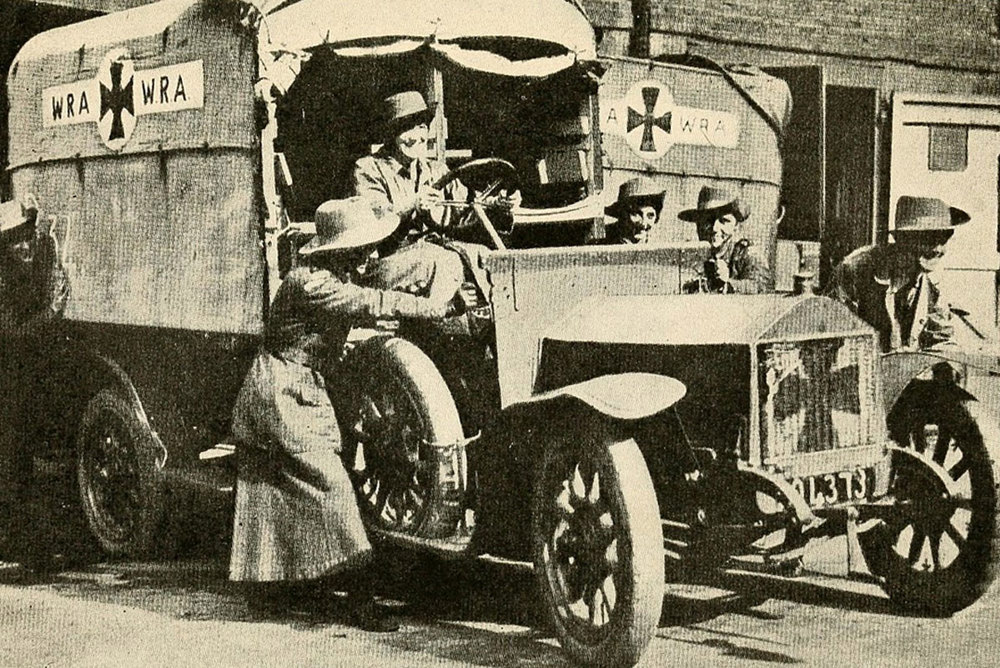

The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (Princess Royal’s Volunteer Corps) was founded by Edward Baker in 1907 to provide assistance to civil and military authorities in time of emergency. Early camps consisted of mainly horse riding and first aid, hence the yeomanry connection.

When the war broke out in 1914, the FANY were quick to offer military assistance, however everyone refused to take them.

Grace McDougall (later Ashley-Smith) was on her way to America when the war broke out and quickly turned back, sailing home. On her journey she met Belgian Minister for the Colonies, who decided that he would have the FANY support the Belgians, if the English would not take them.

McDougall acquired an ambulance and returned with six FANYs. On 27th October 1914 the women crossed to Calais and began ambulance driving for the Belgians and French. Their ambulances were not the best, but they did the job.

Joining the FANYs in Belgium were also the Munro Ambulance Corps, founded by Hector Munro who advertised for “adventurous young women”.

He received two hundred applications, and accepted four.

Throughout their time in the war they endured bombing raids, made supply trips to the front, evacuated the wounded from fires, faced death and disease, and battled with bureaucracy and the patriarchy, nevertheless they stayed cheerful.

In addition to this, they set up regimental aid posts, motor kitchens, and even a mobile bath vehicle.

In 1915 the FANYs were enrolled into the Belgian army. Finally recognising their competence, 1st January 1916, the British War Office asked them to work for Great Britain. Sixteen FANY ambulance drivers replaced the BRCS men.

Surgeon-General Woodhouse uttered “they’re neither fish nor fowl, but damned fine red herring” demonstrating the respect these women gained in the male war arena.¹

Furthermore, these women displayed the upmost perseverance and commitment; the Corps Gazette mentioned how one girl, Pat Waddell, lost a leg when she was hit by a train whilst driving an ambulance, nevertheless, she returned to duty a month later with an artificial leg.

Throughout the war, FANYs were awarded seventeen Military Medals, twenty-seven Croix de Guerre, one Legion d’Honneur, and 11 Mentions in Despatches. The sheer bravery and dedication to the war effort these women demonstrated was rightly recognised; they defied gender stereotypes and put in a strong case for the women’s right to vote. Following the war, the FANY continued to train and from 1921, the War Office provided Army accommodation and training assistance for Annual FANY Camps.

References:

¹ Tom Percy Woodhouse (Surgeon-General), 1915, quoted at The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, ‘History’, The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry [accessed 20/04/2018]

Sources:

Fielding, D., Lady Under Fire on the Western Front: The Great War Letters of Lady Dorothie Feilding MM (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2010), p.2.

The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, ‘History’, The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry [accessed 20/04/2018]

Credits:

Images courtesy of the National Library of Scotland (National Library of Scotland/Flickr)

At Home during the war, women contributed significantly to life on the Homefront. The Women’s Reserve Ambulance (Green Cross Corps) was first on the scene in the wake of London’s first serious zeppelin attack:

‘’There was the time of the first serious Zeppelin raid on London, when amid the crash of falling bombs and the horror of fire flaming suddenly in the darkness, the shrieks of the maimed and dying filled the night with terror and the populace seemed to stand frozen to inaction at the scene about them.

Right up to the centre of the worst carnage rolled a Green Cross ambulance, from which leaped out eight khaki-clad women. They were, mind you, women of the carefully sheltered class, who sit in dinner-gowns under soft candlelight in beautifully appointed English houses.

And they never before in all their lives had witnessed an evil sight. But they set to work promptly by the side of the police to pick up the dead and the dying…” – Mrs. Mabel Potter Daggett.

Women war workers were all demobilised by the spring of 1919, and undoubtedly found it hard to adjust back to pre-war life, after four years of chaos.

Though their contributions to the war were often marginalised in the interwar period, the progress ambulance drivers, munitionettes, nurses, surgeons, and farmers (to name a few), made during the First World War lay the foundations for an even greater contribution women would make in the Second World War.

Sources:

Potter Daggett, M., Women Wanted: the story written in blood red letters on the horizon of the great world war (New York: George. H. Doran Company, 1918), p.73.

Credits:

Image courtesy of The Library of Congress (The Library of Congress/WikiCommons)

The Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC), later Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps, formed a motor branch in mid-1916 under Miss Christabel Ellis, who had driven an ambulance for the French Red Cross in 1914.

On 26th January 1917, the Women’s Interest Committee of the NUWSS wrote to Lord Derby, then Secretary of State for War, regarding the employment of women in the army.

They welcomed the proposal, but believed that controlling large groups of women should be placed in the hands of women themselves. By the end of January, however, it seemed unlikely that the Lawson Report promoting that 12,100 women should be employed in France would go ahead, but women would be made use of.

On the 6th February 1917, it was decided that 12,000 women would take up work in France in various sections, headed by women, but controlled by the army. On the 19th February 1917, the Women’s Branch (AG11) was officially inaugurated and later named the WAAC. On 31st March, the first WAAC women were sent to France battlefields.

The motor drivers of the Mechanical Overseas Section were generally middle class women, who had, most commonly, learnt to drive prior to the war and received lessons from companies such as the British School of Motoring.

The drivers required at least six months experience driving heavy vehicles in order to be recruited, and rather than driving ambulances (the role of the VAD General Service Section), many WAAC drivers were based at the AMTD in Abbeville.

To begin, female drivers in the WAAC were viewed very negatively in the eyes of men, and often found that their tyres had been let down by unaccepting men, fearful of the challenge to such a male-dominated occupation. Eventually, however, men accepted women drivers.

One example of a female WAAC driver was Dolly Shepherd. The first time she had to fix a car, all the men in the garage stopped to watch and cheered when she was successful.

Another time, she came across a Major whose car had broken down. Although he persisted that she would not be able to fix it, she managed to do so with a hairpin as an improvised tool. In the morning, she found a cup of milk left out for her to say thank you.

Sources:

Hansen, A. J., Gentleman Volunteer. The Story of the American Ambulance Drivers in the First World War (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2011), pp.138-139.

Philo-Gill, S., The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in France, 1917 – 1921: Women Urgently Wanted (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, 2017), pp.6-12, 73.

Credits:

Images courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (Imperial War Museum/WikiCommons)

The Result of the women’s role in World War One is significant. Prior to the war, those anti-women’s suffrage believed that women had no right to the vote because they did not engage in the defence of their country, and so could not be considered full citizens.

Despite this, the suspension of activities from Women’s Suffrage Societies, such as the WSPU, demonstrated women’s support for the government and the war effort. Consequently, when the war ended, it would have been obscene for the government to argue that women did not undertake a role worthy of the vote.

Although it is arguable that the clauses of the Representation of the People Act in 1918 were announced as a result of pre-war suffrage efforts, the role women played in the war cannot go unnoticed.

It is, however, important to note that a lot of the women who contributed to the war effort were young, and only women over the age of 30 were granted the right to vote in 1918. In 1918, approximately 8.5 million women registered to vote, of these, only 3,372 women had served in the armed services under the navy or military, including nurses, and members of the WAAC and WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service).

Many may argue that, although women helped to win the war, they had lost the battle of equality. Suffrage leader Millicent Fawcett argued, however, that “the war revolutionised the industrial position of women”.¹

Despite many women losing their jobs in the post-war world, women’s work within the war demonstrated that, ultimately, a woman could do a man’s job.

The NUWSS also took it upon themselves to find work for women who had lost their jobs, and established a Women’s Service Bureau in London. In addition to traditional relief work, they trained women in scientific and technical tasks, such as car maintenance and engineering.

References:

¹ Millicent Fawcett (1918), quoted in Patricia Fara, A Lab of One’s Own: Science and Suffrage in the First World War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), p.11.

Sources:

Fara, P., A Lab of One’s Own: Science and Suffrage in the First World War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp.11, 75.

Philo-Gill, S., The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in France, 1917 – 1921: Women Urgently Wanted (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, 2017), p.145.

Credits:

Images courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (Imperial War Museum/WikiCommons)

Subscribe for updates

Get our latest news and events straight to your inbox.