Segrave and Celebrity

Explore Sir Henry Segrave’s rise to celebrity through tracking how both newspapers and the nation responded to his victories throughout his career.

Henry Segrave’s grit, determination, and British pluck made him a personality who was regularly covered by daily newspapers for his sporting achievements prior to his attempts at land speed records. However, his entry in motor racing was initially overlooked by the daily newspapers.

Henry Segrave’s Early Profile in the Motor Racing Circuit

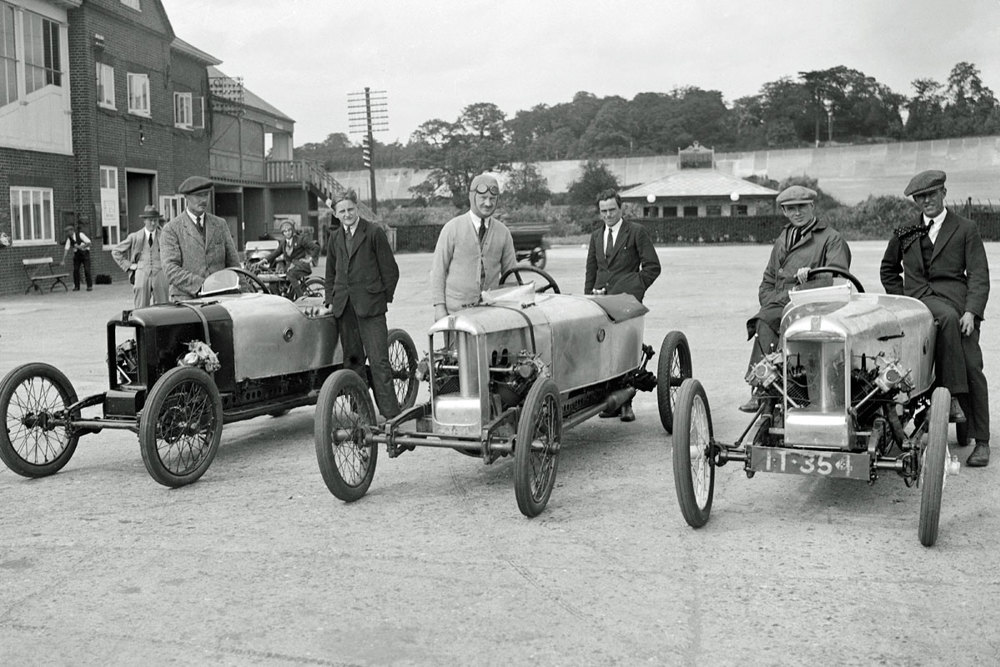

The shadow of the First World War weighed heavily on the British motor racing circuit, with the once busy Brooklands not returning to motor racing until 1920, after extensive repairs to its track. However, interest in motorsport took longer to return, Major Segrave’s first victory as a race car driver in the 1920 Whitsun Sprint was largely overlooked by the daily newspapers.

Instead, some newspapers reported on the spectacle of Segrave’s near miss from severe injury when one of his tyres broke off his car whilst travelling at 90 miles per hour. One exception was the Sheffield Daily Telegraph, which credited Segrave for his ability to safely come to a halt without risk of injury, highlighting his “skill and presence of mind” in averting disaster. These characteristics of grit and determination would reveal themselves again during his 1921 Grand Prix performance.

1921 Grand Prix

Segrave’s reputation as a serious racing driver was proven for some on the 25th of July, when he participated in the 1921 Grand Prix at Le Mans. He was promised a place within the Sunbeam company if he finished the race, but he was beset with troubles before it began.

First, the company he was associated with, Sunbeam Talbot Darroq, withdrew from the race as they feared that their untested cars would underperform. However, Segrave’s single-minded determination led the company to reverse their decision.

The actual race was gruelling as the track surface had been poorly maintained, leading to motorcars churning up rocks striking cars, drivers, and mechanics alike.

Segrave’s greatest difficulty rested with his vehicle’s tyres which were damaged by the loose rocks and required constant replacing. Cyril C. Posthumous, Segrave’s biographer, described one part of the racetrack as ‘looking like a shingle beach’ and recorded that Segrave had to replace his tyres 14 times during the race.

Notably, few newspapers reported on the 1921 Grand Prix, and those that did often withheld any praise and instead asked why the British team were so underprepared.

However, in the motoring press, Segrave was praised for his exertion on the course, with The Autocar describing his efforts as ‘The Labours of Hercules.’ It was not until his victory at Brooklands in September 1921 and France in 1923 when Segrave’s profile across the national press exploded.

Further Reading:

Biss, Gerald. “On the Way to Brooklands : “A.A” Renders Account.” The Sketch. 11th August 1920. British Newspaper Archive. Accessed 12th May 2021. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0001860/19200811/037/0034.

Campbell, Edwin. “Motoring and Aviation.” The Graphic. 1st October 1921. British Newspaper Archives. Accessed 12th May 2021. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/9000057/19211001/044/0030.

Campbell, Edwin. “Motoring Notes: British Withdrawal from French Race.” Sheffield Daily Telegraph. 22nd July 1921. British Newspaper Archive. Accessed 12th May 2021. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000250/19210722/181/0006.

Originator unknown. “Track Racing.” Sheffield Daily Telegraph. 28th May 1920. British Newspaper Archives. Accessed 12th May 2021. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000250/19200528/079/0003.

Posthumus, Cyril. Sir Henry Segrave. London: B.T. Batsford, 1961.

The changing status of Segrave within the motoring press and later daily papers were led by his victories, both international and domestic. Victories in the 1921 Junior Car Club and 1923 Grand Prix increased his celebrity status.

October 1921 Brooklands Victory

Segrave’s career with Sunbeam started after his determined Le Mans performance. Shortly after this development, he finished third in the September Coupe des Voiturettes race. This led to his name appearing in The Times, albeit for a Dunlop advertisement. He was named in the same paper, and other local papers, later the same year, after his victory in the Junior Car Club at Brooklands. These domestic victories were not reported with as much zeal as his later international triumphs.

One thing that did shock the newspapers was the high turnout at the Brooklands race. This growing interest in motor racing helped to popularise Segrave further and explains an increasing number of daily papers reporting his success. This increased popularity enabled him to shape how he was viewed through writing articles and letters to motor magazines like The Motor Owner. At one point, he wrote to this magazine about the importance of engine-tuning. Whilst this participation with the media earned him good will, it was his later 1923 victory that would see his celebrity status dramatically increase.

1923 Grand Prix Victory and Reception

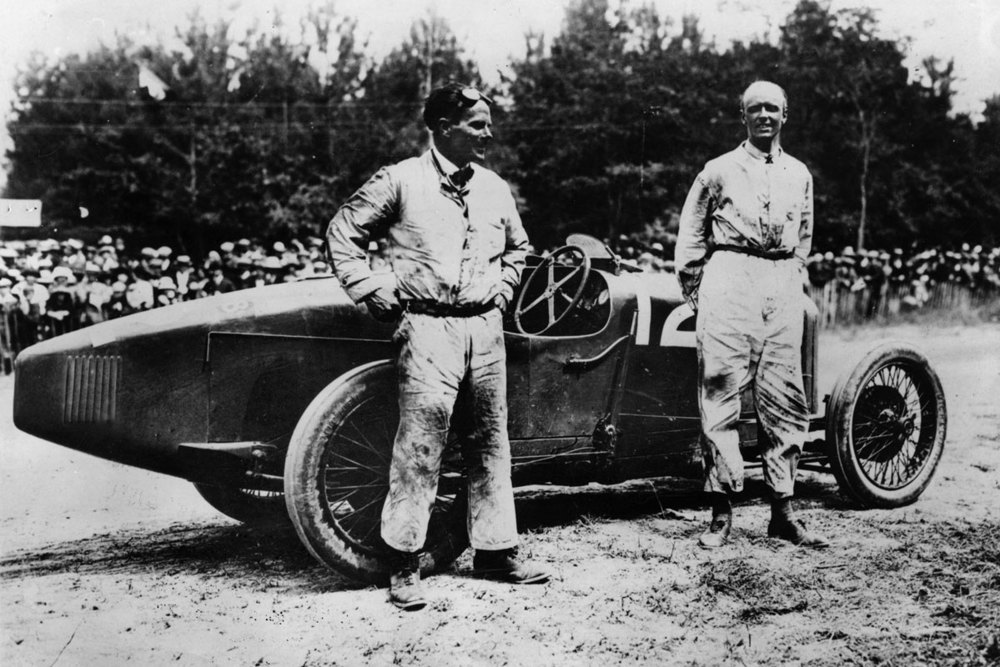

Segrave’s victory at the 1923 Grand Prix in France led to an explosion of publicity. London Illustrated News published photographs of Segrave to stress his central role in this victory.

It was in these pictures, where his physical presence made him a distinctive figure as he stood at over six feet tall: towering over car and mechanic alike.

Other publications, like the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News emphasised his skills as a driver. Sir Jullian Orde, the Royal Automobile Club’s eyewitness, praised Segrave’s abilities.

The Motor further stressed Segrave’s skill, describing the Grand Prix as “anyone’s race from start to finish.”

This made Segrave’s victory even more extraordinary. The paper continued, describing the race as one of “sheer physical endurance.” Such a characteristic fitted nicely with his imposing physical build.

The compliments he received from these publications led to an influx in interest.

Whilst the motoring press celebrated Segrave’s skill, national papers such as The Times focused on the race.

However, Segrave had clearly left an impact as he was invited to contribute to the paper. In 1925, he wrote a Times article unfavourably comparing the quality of British roads to that of French roads at high speeds.

The intervention of Segrave regarding anti-skid surfaces at speed is unsurprising given his own motoring tendencies and later moniker as Britain’s ‘Speed King’.

Further Reading:

Posthumus, Cyril. Sir Henry Segrave. London: B.T. Batsford, 1961.

By the year 1926, Segrave’s celebrity status was in full swing. He had papers reporting on his ambitions in addition to his achievements.

This led to a growing following and such increased fame led to greater authority, with his influence leading to him contributing to The Times with an analysis on the evolution of automobiles.

1926 Land Speed Record

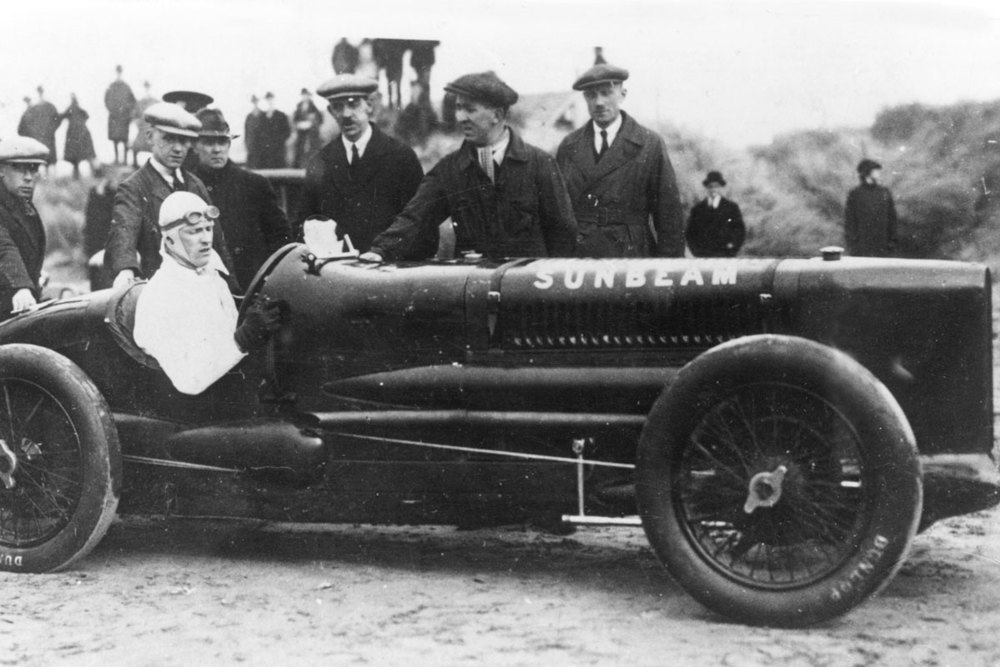

Segrave’s rise during this period was the result of his participation in setting Land Speed Records. His first record was achieved at the Southport Sands: attaining a speed of 152 miles per hour in a 12-cylinder Sunbeam Tiger.

However, this record was met with as much confusion as celebration by the press, with The Times reporting that an attempt had been made on the 16th of March 1926, but not proclaiming that Segrave had in fact broken the one kilometre land speed record. It took the newspaper until the 19th of March to declare that he had achieved a land speed record. Such confusion was down to the fact that the record attempt was meant to take place in early March but had been beset with mechanical problems.

Meanwhile, Southport’s proximity to Manchester and Liverpool meant that regional newspapers paid great attention to Segrave’s presence. In early March, the Liverpool Echo illustrated the technical issues faced by Segrave by reporting that the supercharger on his vehicle had repeatedly failed.

At one point, a mechanical failure during a trial run led to speculation that Segrave had lost control of his vehicle. However, he quickly dismissed this view with an interview with the Liverpool Echo. This intervention shows how this motor-racing champion was determined to maintain his reputation as an excellent and reliable driver.

1927 Land Speed Record

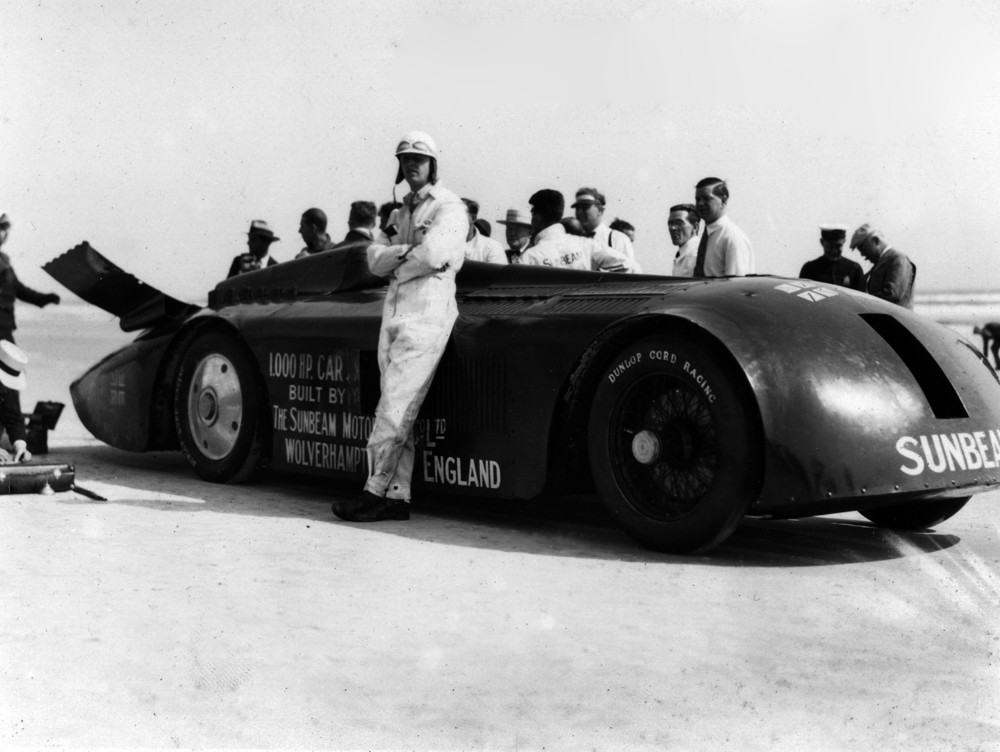

Enormous press interest accompanied the 1927 land speed record attempt, with The Times reporting on the testing of the tyres for Segrave’s Sunbeam car, known affectionately as ‘The Slug’. The Times’ interest was sustained, with them reporting on both Segrave’s early trial runs.

Once the land speed record was reached at 203 MPH, newspapers reacted with jubilation. Segrave’s status as a national icon was solidified and his entire career began to be explored and celebrated.

His time in the Royal Air Force was explored in relation to his success, which added to his sense of bravery.

Many newspapers played on this. For example the Sheffield Daily Telegraph was described as an ‘Airman with a passion for racing’. Again, The Times praised Segrave, publishing a photo of him and titled their article: “Major Segrave’s Success”.

After 1927, Segrave was nothing short of a heroic figure. Papers were increasingly eager to report his ambitions, achievements, and his skills.

The front page of the Westminster Gazette described Segrave’s calm demeanour after his win in Florida and the relief of his wife in England. This emphasis on Segrave’s role in this success shows how he had become a celebrated figure.

Despite his temporary retirement from embarking on land speed records, his return in 1929 with Golden Arrow would see him propelled to the peak of his popularity.

Newspaper Reaction

Segrave’s press exposure after Golden Arrow’s 1929 land speed record was intense. His bravery was seen as all the more extraordinary given American driver Lee Bible’s death shortly afterwards.

This tragedy led newspapers to once again reminisce on Segrave’s career as a fighter pilot in the First World War. By doing so, they positioned him as a patriot, risking his life once more for his country.

Despite being the fastest man alive, having reached a speed of 231 miles per hour, Segrave expressed his belief that he could have possibly reached 240 mph.

However, his team had pointed out that such high speeds inevitably increased his chances of a fatal accident. Despite being the ‘Speed King’, Segrave was always quick to thank his team of mechanics and engineers for his victory and his safety.

In addition to his humility, Segrave always remained calm and collected. When asked about his nerves, he responded that he had none and that the tragedies within the sport did not deter him.

However, it is noteworthy that when he announced his retirement from land speed records, he mentioned that he felt he had used up his good fortune in this dangerous enterprise.

Sir Henry Segrave

During Segrave’s return to England, he was invited to stay in a suite which was usually reserved for royalty on the White Star Liner Olympic.

Another example of Segrave’s skyrocketing popularity was him receiving a telegram which notified him of a pending knighthood for his achievements.

In London, Segrave was met with enormous celebrations. Crowds lined the streets to congratulate him. Taking the speed record back from America was seen as an incredibly patriotic act.

He later stated that this was his goal to the press, stating: “It is a matter of indifference to me who holds the World’s speed record as long as it is held by an Englishman.”

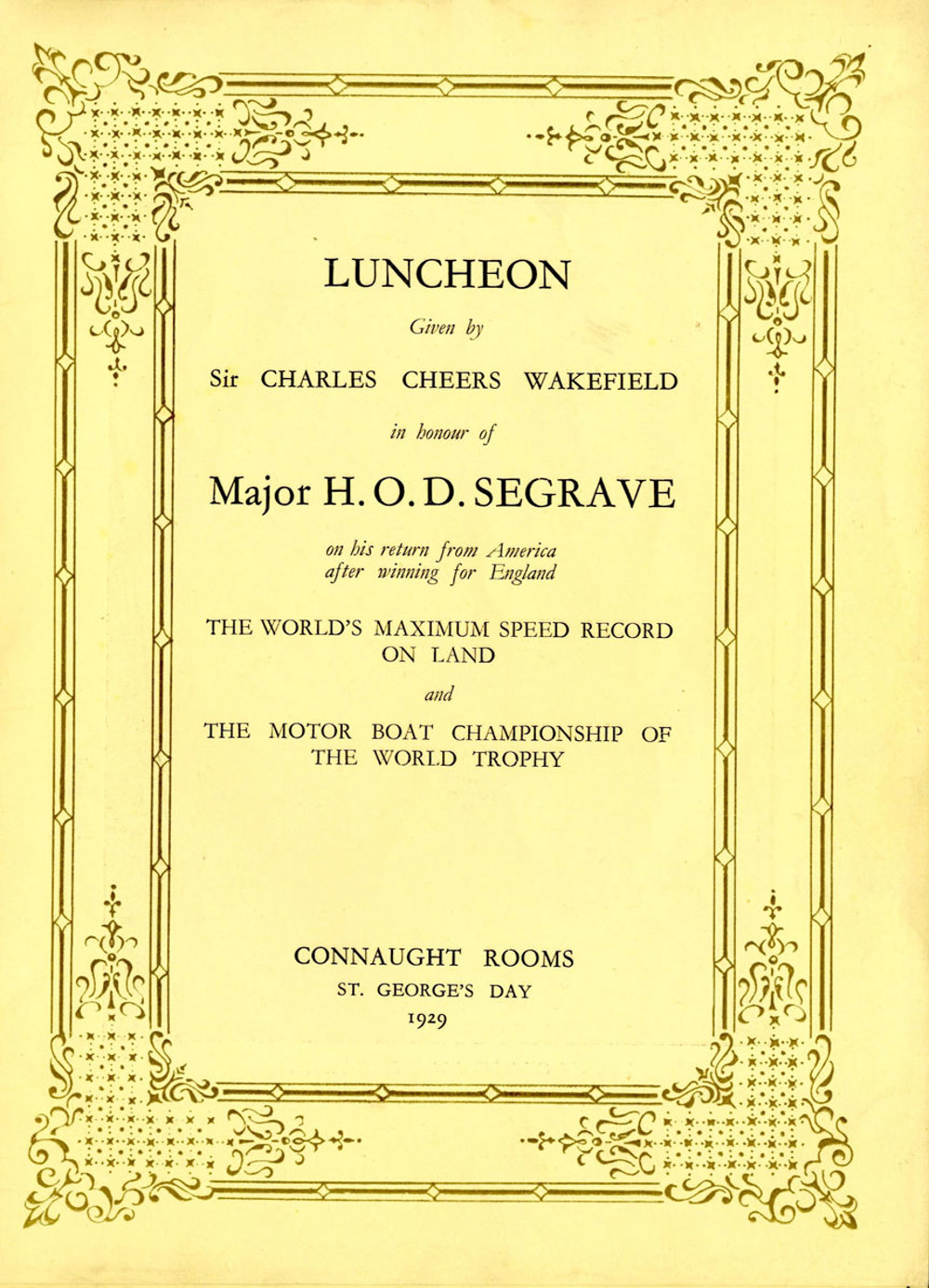

On April 23rd 1929, there was a Luncheon held for Segrave. This was hosted at Connaught Rooms and many senior political figures in attendance, including the Home Secretary, William Joynson-Hicks. Lord Wakefield toasted Segrave as the guest of honour.

In a twist of irony, the World’s fastest man arrived late to his knighthood, having underestimated the journey to Craigweil House!

In response to King George V’s remonstrations, Segrave replied that he was held up by three level crossings. The King humorously replied: “A speed King—held up by a mere railway train!”

Notably, Segrave avoided the press during his knighthood by leaving through the tradesmen’s door, perhaps out of embarrassment at the huge surge of recognition.

Despite this avoidance, he later used his celebrity status to pursue his own engineering and political interests.

Segrave’s Achievement Celebrated

The all-British nature of Golden Arrow led to the achievement being celebrated by the general public.

The distinctive shape of the car led to a number of toy companies hoping to benefit from this by producing miniature versions of the vehicle. These companies ranged from Kingsbury Toys to Automotives Geographical.

Kingsbury’s toys were endorsed by Segrave and their Golden Arrow miniatures remain a collector’s item.

Notably, Golden Arrow was no stranger the small scale, with Chief Engineer John Samuel Irving having built a model to test its aerodynamic potential in a wind tunnel.

The Press and Sir Henry Segrave

The brand surrounding Sir Henry Segrave had shaped how he was perceived by the press. After 1929, the ‘Speed King’ and his ambitions were closely followed by newspapers.

An example of this was The Scotsman publishing photos of him practicing just prior to his victory in the Crown Prince of Italy’s Cup, with a record speed of 92.8 miles per hour.

As the celebrations tapered off, Segrave’s focus turned to water speed records. His favoured boat was the Miss England, which is pictured below.

Once again, the danger of such a sport led Segrave to being cast as a national hero, risking life and limb for the sake of his country.

Such celebrity status led to Segrave’s personal life falling under greater scrutiny, with the Sheffield Independent featuring a front-page photograph of him as the best man at his brother’s wedding. This greater popularity gave Segrave increasing influence and made him a valuable ally to seek out.

Sir Henry Segrave’s Politics

As a result of his remarkable accomplishments, Segrave’s words carried weight outside of motorsport and he was unafraid to intervene in political matters.

For instance, he was vocal about his support for the Empire Free Trade Crusade, led by Lord Beaverbrook. This political party demanded that Britain adopt a free trade stance with Commonwealth countries.

Segrave’s support of Lord Beaverbrook raises interesting questions. Beaverbrook was a powerful media mogul who owned the Daily Express, a daily newspaper which became increasingly influential during the 1930s.

Therefore, further investigations may reveal whether positive coverage of Segrave in the Daily Express was a result of his political support.

However, Segrave’s popularity should not be easily dismissed or mistakenly explained as the result of political dealings: he received favourable coverage from a broad range of newspapers, the public, and private enterprise for his achievements.

The Blackburn B-1 Segrave and Modern Comparisons

Such achievements also gave Segrave the opportunities to work on his own projects: aircraft design in particular.

He understood how these machines worked due to his experience as a pilot and driving Golden Arrow.

Shortly after his success, he partnered with the Blackburn Aircraft Company to design a touring monoplane, which was fittingly named the B-1 Segrave.

Whilst newspapers such as the Yorkshire Evening Post described the plane as a ‘fast and efficient machine’, it had limited commercial success.

In part, this was due to Segrave’s unfortunate and sudden death on Lake Windemere on the 13th June, with the B-1 Segrave having made its maiden flight less than a month prior.

Without the star power and celebrity endorsement of the Speed King, the model failed to capture the imagination of potential buyers.

A modern comparison to a popular motorsport figure using their celebrity to embark on personal projects is Sir Lewis Hamilton, who founded a racing team called X44 in early September 2020.

This team is part of the Extreme E Organisation, which hosts races in remote locations using electric vehicles in order to highlight how these environments are affected by climate change.

Further Reading

British Aerospace Engineering Systems. “Blackburn B-1 Segrave: A Twin Engine Light Commercial Aircraft Originating with Sir Henry Segrave.” BAE Systems: Heritage. Accessed 20th May 2021. https://www.baesystems.com/en/heritage/blackburn-b-1–ca18-and-ca20–segrave.

Subscribe for updates

Get our latest news and events straight to your inbox.